Preface

Briefing description and more.

This briefing provides an overview of veganism, the history of vegan thinking, and reasons to consider veganism.

Companion Videos

Briefing Meta

Counts:

| Main Text | |

| Key Points | 8 |

| Counterclaims | 1 |

| Supplementary | 2 |

| Further Study | 6 |

| Footnotes | 149 |

| Media & Advocacy | |

| Advocacy Notes | 13 |

| —Socratic Questions | 19 |

| Flashcards | 148 |

| Presentation Slides | 62 |

| Memes & Infographics | 2 |

| Companion Videos | 1 |

Activity Log:

Key Points Links

Loading…

Help Us Improve

Please send your suggestions for improvements, or report any issues with this briefing to team@vbriefings.org

We appreciate that you are taking the time to help us improve. All suggestions and reports will be carefully considered.

Summary

A concise summary of the briefing (see below for citations).

Veganism is about living in a way that avoids contributing to the injustices and cruelty toward other animals by making ethical choices in our daily lives. It’s grounded in ethics while also recognizing benefits to the planet and human health.

The movement began by name in 1944, but its principles trace back to figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Mahatma Gandhi.

Major health organizations recognize vegan diets as not only nutritionally adequate but also health-promoting, while research shows they are the most sustainable choice, reducing the environmental impacts of animal agriculture.

By confronting systemic exploitation and suffering through advocacy for other animals, veganism aligns with social justice and ethical frameworks, offering a clear and compassionate way forward.

Summary by Section

History. Historical figures practiced the ideals of veganism long before Donald Watson coined the word “vegan” in 1944. Such figures include Pythagoras, Leonardo da Vinci, Mahatma Gandhi, and others.

Animal Injustices. Despite humane-sounding labels and certifications, farmed animals suffer many injustices and abuses before they are violently slaughtered while still young. These abuses include horrid living conditions, painful mutilations, denial of their natural behaviors, debilitating selective breeding, reproductive violations, cruel handling, and violent, painful slaughter.

Health. Leading dietetic associations in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia—as well as major medical institutions, such as Harvard Public Health, Mayo Clinic, and Cleveland Clinic—have all stated that a vegan diet is not only sufficient but also promotes health and helps prevent chronic disease.

Environment. Studies show that vegan diets have the smallest environmental footprint. It’s widely agreed that animal agriculture is extremely destructive and contributes heavily to global warming, habitat destruction, deforestation, water waste, water and air pollution, biodiversity loss, desertification, ocean dead zones, and fecal contamination.

Social Justice. Veganism has been a social justice movement from the start, recognizing that all forms of oppression are related, whether inflicted on humans or other animals. But veganism is also a social justice movement in another sense: it challenges an industry—animal agriculture—that disproportionately harms poor and marginalized people.

Philosophical Frameworks. The deontological rights-based approach, utilitarianism, virtue ethics, and the ethics of care, when followed to their logical conclusion, all support veganism.

Finally. The case for veganism is simple, the objections to veganism are weak, and getting started may be easier than you think.

Context

Places this topic in its larger context.

As veganism grows globally, it challenges existing systems and paves the way for change across society.

Through the lens of veganism, we can reimagine our relationship with the planet and its inhabitants—and align our actions with the values we hold dear. This is especially important in a world that’s growing increasingly aware of not only the injustices we inflict on animals but also the climate change and resource scarcity we inflict on the planet.

Key Points

This section provides talking points.

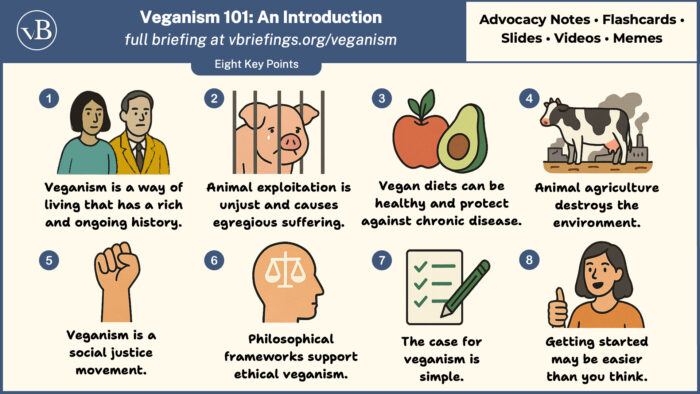

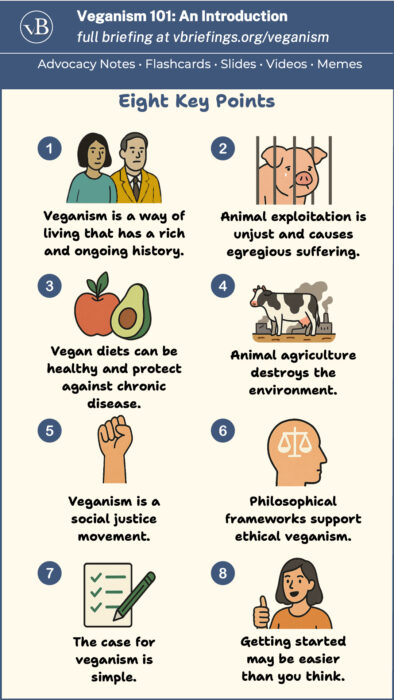

Veganism is a way of living that has a rich and ongoing history.

Before the Word “Vegan” (proto-veganism)

Note: We refer to proto-veganism as the early historical or cultural practices, philosophies, or diets that resemble or anticipate modern veganism, even if they predate the formal term “vegan.”

The word “vegan” may be relatively new, but the idea isn’t. Veganism is just one point on a historical continuum of human concern for other animals.

Long before factory farming and long before the word “vegan,” prominent historical figures saw that exploiting animals requires animal suffering, and they embodied vegan ethics in their writings and actions.

Pythagoras (570–495 BCE)

- Pythagoras, an influential Greek philosopher and mathematician, invented the word “philosophy,” first called the universe the “cosmos,” and first used the word “theory” in the way it’s used today. He’s perhaps best known for the Pythagorean Theorem.1

- Pythagoras believed humans and other animals have a special kinship. He refused to eat animals not because of their intelligence but because of their capacity to feel pleasure and pain.2

- Pythagoras had followers known as Pythagoreans. Until the 19th century, when the word “vegetarian” came into use, the Pythagorean diet meant what “vegetarian” means now.3

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- Leonardo da Vinci was a quintessential Renaissance polymath, renowned for his mastery of art, science, engineering, and painting. Da Vinci was ahead of his time, not only in designing bicycles, airplanes, and helicopters but also in his attitude toward animals. According to one biographer, he was “a man imbued with an uncommon compassion for all living things.”4

- Leonardo da Vinci said he would not let his body become “a tomb for other animals, an inn of the dead…”5 He loved animals, refused to eat them, and abhorred the thought of hurting them.6

- In the open markets of Florence, Leonardo da Vinci frequently bought caged birds just to release them, giving back their freedom.7

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)

- Shelley was a major English Romantic poet known for his lyrical poetry. His works, including “Ozymandias,” “Prometheus Unbound,” and “To a Skylark,” reflect his passion for political and social reform, as well as exploring nature and the human condition. Shelley’s idealism and imaginative style helped shape future literary movements.

- Shelley, who one biographer calls the first celebrity vegan,8 regretted that “beings capable of the gentlest and most admirable sympathies, should take delight in the death-pangs and last convulsions of dying animals.”9

- He wrote a book, A Vindication of Natural Diet, which uses comparative anatomy to show that vegetable diets suit humans best.10

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910)

- Leo Tolstoy was a Russian novelist, philosopher, and social reformer, best known for his epic novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, which explore complex themes of history, morality, and the human experience. He is a leading figure in realist literature and one of the most important literary and philosophical minds of the 19th century.

- Tolstoy wrote a book titled The First Step: An Essay on the Morals of Diet, which called abstaining from animal foods the first step toward moral perfection.11

- He says using animal foods “is simply immoral, as it involves the performance of an act which is contrary to the moral feeling—killing; and is called forth only by greediness and the desire for tasty food.12

- He also condemns self-delusion, saying, “we are not ostriches, and cannot believe that if we refuse to look at what we do not wish to see it will not exist.”13

George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950)

- George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright, critic, and polemicist renowned for his sharp wit and social commentary. His plays, such as Pygmalion, tackle issues such as class, feminism, and religion. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925.

- Shaw was one of many to connect animal slaughter to the lack of world peace, saying, “While we ourselves are the living graves of murdered beasts, how can we expect any ideal conditions on this earth?”14

- Shaw is credited with the famous quote, “Animals are my friends…and I don’t eat my friends.”15

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

- Mahatma Gandhi led India’s nonviolent struggle for independence from British rule. He developed and popularized nonviolent resistance, which inspired civil rights movements worldwide—and leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Gandhi believed “the more helpless a creature, the more entitled it is to protection by man from the cruelty of man.”16

- As a young law student in London, he made spreading vegetarianism (the animal ethics standard of the time) his mission,17 and he carried out that mission by writing essays and giving speeches.18

- It seems he honed his activism skills by being a voice for animals and then used those skills to change the course of human history.

The Birth of a Movement

Donald Watson, perhaps with the help of his wife Dorothy or others, coined the word “vegan” in 1944. “Vegan” was formed using the first three letters and last two letters of the word “vegetarian.” That same year, the Vegan Society was formed.19

Watson was unhappy that “vegetarian” had morphed to include dairy, and he thought a new word for “non-dairy vegetarian” was needed.20

The Vegan Society’s definition of “veganism” changed over the years, but by 1988, it settled as the one most cited today: “a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing, or any other purpose.”21

This first issue of the Vegan Society newsletter was published in November, 1944.22 The Vegan Society is still active today.23

In the first issue of the Vegan Society newsletter, Watson predicted humankind would eventually “view with abhorrence the idea that men once fed on the products of animals’ bodies.”24

Animal exploitation is unjust and causes egregious suffering on a massive scale.

Note: See our briefing “Animal Agriculture: Cruel and Unjust” for more details, or our even more focused briefings on cows, pigs, chickens, and fish. Future briefings will address the exploitation of animals in entertainment, clothing, sport, and research.

Slaughter is unjust even if done suddenly and painlessly (which it is not).

Slaughter, even if sudden and painless, is unjust because it deprives an individual of their future experiences, choices, and right to live.

Life has inherent value, and ending it disregards the moral worth of the being, regardless of the method.

The harm of killing goes beyond physical suffering; it is the fundamental injustice of taking away a life that is valued and could have continued.

Because we have no nutritional need for meat, dairy, or eggs, the deaths those products require are unnecessary, as is the suffering.

Exploited animals suffer many abuses.

Below is just a sample of the abuses farmed animals face—abuses that also cause stress, depression, and poor mental health.25

Violent Slaughter: Shooting | Maceration | Throat Slitting

- Slaughter methods such as throat slitting, shooting, maceration, electrocution, and gassing inflict extreme suffering, often causing prolonged pain, suffocation, internal burning, or severe bodily trauma due to ineffective stunning and high-speed processing.2627282930313233

Horrid Living Conditions: Confinement | Crowding | Fecal Filth

- Farm animals endure extreme confinement, standing in waste-filled enclosures, packed so tightly they cannot move, and suffer from respiratory issues, oxygen deprivation, and disease due to overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.343536373839

Painful Mutilations: Debeaking | Dehorning | Tail Docking | Castration

- Farm animals undergo painful mutilations, including beak trimming, castration, tail docking, ear notching, and dehorning, often without anesthetic or pain relief.4041 424344454647

Denial of Natural Behaviors: Free Movement | Courtship | Sex | Roosting | Rooting | Nurturing and Being Nurtured | Playing | Teaching

- Farm animals are often separated from their offspring, causing distress and long-term anxiety, while extreme crowding prevents natural behaviors, leading to constant fear and stress..484950515253

Debilitating Selective Breeding: Larger Breasts | More Milk | More & Bigger Eggs

- Farm animals are bred for more and larger eggs, larger breasts, excessive milk, and more muscle, causing osteoporosis, broken bones, uterine prolapse, deformities, heart attacks, metabolic diseases, and high mortality rates.5455565758596061

Reproductive Violations: Semen Collection | Insemination | Separation of Offspring

- Farm animals endure painful semen collection through electro-ejaculation or forced mounting, while artificial insemination involves invasive procedures that require manual penetration and cause significant stress and discomfort.626364

Cruel Handling: Beating | Prodding | Transportation | Maceration | Slaughter

- Farm animals suffer violent handling during transport and confinement, often grabbed, thrown, and crammed into crowded spaces, leading to broken bones, suffocation, and severe injuries. Many endure beatings, kicks, and other physical abuse, causing pain, fear, and lasting harm.6566676869

Downers: Dragging | Electrocution | Forklifting | Spraying | Left to Die

- Farm animals who are too weak or injured to stand are often denied veterinary care, beaten, dragged, electrocuted, rammed with forklifts, or simply left to die.70717273

Farmed animals are slaughtered very young, after living only a fraction of their natural lifespans.

Animals slaughtered for meat live only 2%–7% of their natural lifespan, laying hens live less than 20% of their natural lifespan, and dairy cows live 30% of their natural lifespan.747576777879

Humane-sounding labels and certifications are deceptive and largely meaningless.

Humane labels and certifications are a form of humane washing, deceiving consumers by portraying animal products as ethical while hiding the reality of suffering. Investigations by Consumer Reports and the Open Philanthropy Project found that terms like cage-free, free-range, and pasture-raised are largely meaningless, with audits that are infrequent, ineffective, and rarely enforced.80818283

Even the highest-tier certifications allow for extreme confinement, lack of exercise and socialization, genetic modifications that cause health issues, and routine practices such as separating calves from their mothers and mass-killing male chicks.”84

The scope of suffering, as indicated by the numbers slaughtered, is beyond imagination.

The scale of suffering is immense, with over 70 billion land animals slaughtered each year (FAO85)—99% from factory farms(Sentience86).

The yearly slaughter toll exceeds the total number of humans who have ever lived.

Calculation Details

Public Broadcasting Radio estimates that as of 2022, the total number of humans who have ever lived on Earth is 117 billion.87

Annually, over 70 billion land animals88 and 51 to 167 billion fish89 are slaughtered.

The root of the problem is viewing animals as mere things with no inherent worth—that exist only for humans and for maximizing profit.

Industry publications openly depict farm animals as machines, such as those stating that pigs should be treated like factory equipment and that sows’ purpose is “to pump out baby pigs like a sausage machine.”9091

Vegan diets can be healthy and protect against chronic disease.

Note: See our briefing titled “Vegan Diets Can Be Healthy and Protective Against Chronic Disease” for a more detailed look at vegan diets.

Prominent health organizations embrace a vegan diet.

Mayo Clinic,92 Harvard Public Health,93 Cleveland Clinic,94 Kaiser Permanente,95 NewYork-Presbyterian,96 and others have all said plant-based diets are not only sufficient but also promote health and help prevent chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and high cholesterol.

Cleveland Clinic said, “There really are no disadvantages to a herbivorous diet!” and “Obtaining proper nutrients from non-animal sources is simple for the modern herbivore.”97

Kaiser Permanente even advises their doctors to recommend a plant-based diet to their patients, especially those with high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or obesity.98

Dietetic associations endorse a vegan diet.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics is the largest nutrition-focused organization in the world, with over 100,000 credentialed professionals.99 Their 2025 formal position statement endorses well-planned vegan diets as healthy and nutritionally adequate for adults, and says that “…vegan dietary patterns can be recommended by RDNs [Registered Dietitian Nutritionists], when appropriate, for prevention and management of some chronic diseases…”100

The dietetic associations of other countries, including Canada,101 England,102 and Australia,103 have made similar statements.

Various plant-based initiatives have shown excellent results.

Plant Pure Nation

The Plant Pure Nation initiative went into various rural communities and fed people veganized versions of standard dishes.104

Participants experienced significant improvements in key health markers, such as reductions in cholesterol levels, blood pressure, blood sugar, triglycerides, and body weight. Many reported better energy levels and a decrease in reliance on medications.105

The Ornish Reversal Program

Dr. Ornish’s program106 has been implemented in numerous hospitals and is approved by Medicare.107

It is the only program scientifically proven in randomized controlled trials to reverse the progression of even severe coronary heart disease without drugs or surgery.108

All essential nutrients can be obtained without consuming animal products.

When major health organizations, research institutions, and dietetic associations all say we have no nutritional need for animal products, we’ve reached a scientific consensus.

Animal agriculture destroys the environment.

Note: See our briefing titled “The Environmental Impact of Animal Agriculture” for a more detailed look at animal agriculture’s environmental impacts.

Scientists agree that animal agriculture is a major driver of environmental destruction.

The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) called meat the “world’s most urgent problem” and said, “our use of animals as a food-production technology has brought us to the verge of catastrophe.”109

The Worldwatch Institute said, “The human appetite for animal flesh is a driving force behind virtually every major category of environmental damage now threatening the human future.110

An article in Georgetown Environmental Law Review sums it up nicely, calling animal agriculture the “one industry that is destroying our planet and our ability to thrive on it.”111

Vegan diets have the smallest environmental footprint.

An analysis using data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) determined that vegan diets have roughly half the environmental footprint of a meat-centric diet and 60% the footprint of the average American diet.112

Findings published in the journal Nature Food in 2023 showed that plant-based diets, compared to meat-rich diets…113

- produce ~75% fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

- use ~54% less water.

- use ~75% less land.

Animal agriculture’s devastation is far-reaching.

Livestock or animal agriculture’s contribution to global warming varies from 14.5% to 87% depending on the assumptions made. The higher numbers include the lost opportunity cost of carbon sequestration through reforestation, which is reasonable to include.

Animal agriculture is not only a leading cause of global warming but also contributes greatly to habitat destruction, deforestation, water waste, water and air pollution, biodiversity loss, desertification, ocean dead zones, and fecal contamination.114

Animal agriculture is responsible for 80% to 90% of Amazon rainforest destruction (Yale115 and World Bank116).

Livestock overgrazing is the single greatest cause of desertification worldwide, according to a study published in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources.117

According to a 2023 study published in Nature Communications, reduced air pollution due to plant-based diets could save over 200,000 human lives per year.118

Biomass research puts animal agriculture’s dominance of the planet in perspective.

A 2018 study titled “The biomass distribution on Earth” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), as analyzed by Our World in Data, revealed the following:119

- Of all the mammal biomass on Earth, 62% is farm animals, 34% is humans, and 4% is wild animals.

- The total weight of chickens on farms is approximately 2.5 times the total weight of all wild birds.

- Humans and livestock combined outweigh wild mammals by about 24 to 1.

Animal agriculture’s environmental harm stems from its inefficiency.

Animal agriculture is so inefficient because most of the calories farmed animals consume go toward the animals’ daily living. Also, some calories they consume go toward growing body parts that are not consumed (Applied Animal Nutrition Journal120).

On average, it takes 24 calories of plant-based feed to produce 1 calorie of animal-based food (World Resources Institute, “Creating a Sustainable Food Future”121).

Animal agriculture uses 83% of global farmland while producing only 18% of the total calories and 37% of the protein calories that humans consume (2018 study from Oxford122).

From an environmental perspective, reducing animal agriculture is crucial.

The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) said, “A substantial reduction of [harmful environmental] impacts would only be possible with a substantial worldwide diet change, away from animal products.”123

Sir David Attenborough, broadcaster and naturalist, said,

“We must change our diet. The planet can’t support billions of meat-eaters.”124

Veganism is a social justice movement.

Veganism is a social justice movement in two significant ways. The first concerns how human injustices arise from using animals for food; the second concerns its commonalities with all forms of oppression.

Human social injustices arising from using animals for food production.

Animal agriculture leads to food sequestering and shortages, while veganism does the opposite—mitigating global hunger and starvation—as shown in our briefing on the topic.

Climate change, in which animal agriculture plays a significant role, disproportionately affects the poor, as they are more vulnerable to natural disasters, crop yield losses, and other tragedies.125

Slaughterhouse workers suffer from high rates of injuries, infections, illnesses, and PITS (Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress), a form of PTSD126

Rates of violent crime, including domestic abuse and rape, are higher in communities near slaughterhouses.127

One example of animal agriculture’s environmental injustice comes from North Carolina, where the feces and urine of 9.5 million swine from over 2,000 high-density farms are stored in open-air cesspools. Due to this inadequate storage, the waste is sprayed into fields and drifts into the yards and homes of the poor community nearby. This results in not only foul odors but also asthma attacks, bronchitis, and runny noses and eyes.128 After decades, the problem still persists.129

Social justice is anti-oppression.

Veganism has been recognized as a social justice movement since the movement’s beginning in 1944.

- In the first issue of the Vegan Society newsletter, The Vegan News, Watson says, “We can see quite plainly that our present civilization is built on the exploitation of animals, just as past civilizations were built on the exploitation of slaves…”130

The various forms of oppression, whether of humans or other animals, share common mechanisms and structures. All forms of oppression use power dynamics, social hierarchies, and cultural norms to objectify, dehumanize, hurt, and control.131132

A. Breeze Harper (aka Sistah Vegan), Carol Adams, and other ecofeminists have written extensively on how various forms of oppression are connected.133134

Joaquin Phoenix, during his Academy Award acceptance speech in 2020, summarized this connection:

- “I see commonality. Whether we’re talking about gender inequality or racism or queer rights or indigenous rights or animal rights, we’re talking about the fight against injustice. We’re talking about the fight against the belief that one nation, one people, one race, one gender or one species has the right to dominate, control and use and exploit another with impunity.”135

Philosophical frameworks support ethical veganism.

The Deontological Rights-Based Approach

Tom Regan, in his book The Case for Animal Rights (1983), argues that animals are “subjects of a life” and thus possess inherent value, making animal exploitation morally impermissible, regardless of the circumstances.136

Tom Regan says, “The philosophy of animal rights stands for, not against, justice. We are not to violate the rights of the few so that the many might benefit. Slavery allows this, child labor allows this, all unjust social institutions allow this, but not the philosophy of animal rights, whose highest principle is justice.”137

See The Rights-Based Approach to Animal Ethics for more on this framework.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism, a philosophical framework developed by Jeremy Bentham and later expanded by John Stuart Mill, supports the end of animal exploitation by emphasizing the principle of the greatest happiness for the greatest number.138

Jeremy Bentham famously applies this principle to animals: “The question is not, can they reason, nor can they talk, but can they suffer?139

Peter Singer, a contemporary philosopher, applies utilitarianism to animal ethics in his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975), arguing that causing animals unnecessary suffering for human benefit is ethically unjustifiable. He applies the concept of “equal consideration of interests.”140

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics, first articulated by Aristotle, focuses on the moral agent’s character rather than specific actions or consequences.141

In the context of animal ethics, philosopher Rosalind Hursthouse argues that a virtuous person would be compassionate and kind toward animals—and oppose practices that cause suffering.142

The Ethics of Care

The ethics of care, developed by feminist philosophers like Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings, emphasizes the importance of relationships, empathy, and care in moral decision-making. This approach argues that ethical considerations should be grounded in the nurturing of relationships and the well-being of others, including animals.143

From an ethics of care perspective, exploiting animals is wrong because it neglects our responsibility to care for and protect vulnerable beings who depend on us.144

The case for veganism is simple.

We have shown that plant-based diets can be healthy and protect against chronic disease and that exploiting animals greatly harms the environment and causes suffering on a massive scale.

If you can live a healthy life without the culpability of paying others to breed, mistreat, and violently kill animals, why wouldn’t you?

By living vegan, you prevent the suffering and slaughter of many innocent lives who would’ve been born or hatched into a system of violence.

An analysis by Animal Charity Evaluators concluded that a person can spare 105 vertebrates a year by going vegan.145 A popular vegan calculator, using different assumptions, estimates the total number of animals (not just vertebrates) spared annually to be over 300.146

Getting started may be easier than you think.

Many vegans once said, “I could never be vegan.” Our briefing, Getting Started with Going Vegan, provides helpful suggestions that will send you on your way.

Counterclaims

Responses to some yes but retorts.

Claim: Veganism is invalid because [fill in the blank].

The objections to veganism are weak and often based on inadequate research, bad logic, or irrelevant arguments.

We cover the most common objections to veganism in our growing objections section. More such briefings are on the way.

Supplementary Info

Additional information that may prove useful.

Veganism is on the rise.

Veganism’s rising popularity is reflected in the rapidly growing number of vegan options in restaurants, grocery stores, clothing stores, and cosmetics, as well as the proliferation of vegan celebrities, public figures, and professional athletes.147 Veganism is becoming mainstream.148

According to the high-dollar market research firm Global Data, between 2014 and 2017, the number of vegans in the U.S. grew fivefold (500%).149

The meat industry not only harms animals.

Video: Inside the Meat Industry

Further Study

Sources providing a deeper understanding of the topic or related topics.

Other Resources

“Veganism in 2025: Breaking Barriers, Building Change” by Michael Corthel discusses the significant advancements and societal shifts in veganism by 2025, highlighting the growing mainstream acceptance, innovative food technologies, and the positive impacts on health, environment, and animal rights and welfare.

The Vegan Society’s History page outlines the organization’s history, from its founding in 1944 by Donald Watson to its ongoing mission to promote veganism.

Advocacy Resources

Information to help with outreach and advocacy.

Share This Briefing

Cloned from the Preface Section on page load.

Companion Videos

Cloned from the Preface Section on page load.

Additional Visuals

How to use Additional Visuals

Feel free to share these visuals on social media or anywhere they might prove useful.

Click on an image to get an enlarged view, then right-click to save or copy to the clipboard. From an enlarged view, click on the ‘X’ in the upper right corner to exit the enlarged view and return to the visuals gallery.

Visuals Gallery

Presentation Slides

Click the link to view and optionally download the companion PowerPoint Slides for this briefing:

How to Use the Presentation Slides

Feel free to use and customize these slides for your own presentations. You can also mix this deck with slides from other briefings to build a custom presentation.

After clicking on the share link , you can view the slides and speaker notes. You can also download the PowerPoint file for editing and customization—just look for the download link. If you have a Microsoft account with OneDrive access, you can also save the slides to your personal onedrive.

Flash Cards

We partner with Brainscape for its excellent learning features. You will need to create a free Brainscape account to study the cards.

Go to Flash Cards: This will take you to a list of decks.

About Flash Cards and Brainscape

Flash cards are here to help you commit important facts and concepts in this briefing to memory.

In Brainscape, there is one deck for each briefing. You can study more than one deck at a time. Brainscape uses spaced repetition to promote memory retention. It is “the secret to learning more while studying less.”

You can study using your browser, but Brainscape also has a free mobile app that makes learning anywhere easy.

Socratic Questions

Socratic-style questions are embedded in the Advocacy Notes below, and shown in italics.

These are open-ended, thought-provoking questions designed to encourage critical thinking, self-reflection, and deeper understanding. They are inspired by the Socratic method, a teaching technique attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, who would ask his students probing questions rather than directly providing answers.

The goal is to help people examine their beliefs, clarify their thoughts, uncover assumptions, and explore the evidence and reasoning behind their ideas.

Advocacy Notes

Elevator Pitch

The first four paragraphs in the Summary section make for an excellent forty-second elevator pitch. Here is an even more condensed version for a seventeen-second pitch:

- Veganism is about living in a way that avoids contributing to the injustices and cruelty toward other animals by making ethical choices in our daily lives. It’s grounded in ethics while also recognizing benefits to the planet and human health. And by advocating for other animals, it aligns with other social justice movements, offering a clear and compassionate way forward.

Tips for Advocacy and Outreach

General Tips and Observations

- This briefing is not only a core briefing but also the foundation of the briefing hierarchy, in the sense that many of the other briefings expand on this one.

- This briefing, together with the other core briefings and the objections briefings, provide essential knowledge that will go a long way in preparing you to discuss veganism with others.

- The Socratic-style questions shown here are broad and general—the topic is just too large for anything more. See the Advocacy Notes sections of other briefings for more detailed responses.

- Since many people have little knowledge about what veganism actually is, your role in outreach is to make it accessible, compelling, and aligned with their values.

- Don’t present historical figures as vegan because the supporting evidence is sketchy. Say instead that they anticipate modern veganism with a concern for animals ahead of their time.

Show That Veganism Is About Ethics, Not Just Diet

People often think veganism is just a diet rather than a way of living and a movement to minimize harm.

- “If we can live without harming animals unnecessarily, why wouldn’t we?”

- “Veganism isn’t about personal purity—it’s about reducing suffering. Does that align with your values?”

Why? This shifts the focus from food choices to ethical responsibility.

Make It Clear That Veganism Has a Long History

Many assume veganism is a modern trend, but it has deep historical roots.

- “Did you know figures like Pythagoras, Leonardo da Vinci, and Gandhi rejected eating animals long before the term ‘vegan’ existed?”

- “’Vegan’ as a word didn’t appear until 1944—but it’s part of a long tradition of people questioning the ethics of exploiting animals. Why do you think so many great thinkers took this stance?”

Why? This shows that concern for animals isn’t new or extreme—it’s a long-standing moral stance.

Highlight That Major Health Institutions Support Vegan Diets

People worry that vegan diets are nutritionally inadequate, but major health organizations disagree.

- “Did you know the world’s largest dietetic association, The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, says a well-planned vegan diet is healthy and protective against some diseases?”

- “If the Mayo Clinic, Harvard Public Health, and the Cleveland Clinic all say plant-based diets promote health and prevent disease, does that change your perception?”

Why? This combats the misconception that veganism is unhealthy or extreme.

Connect Veganism to Environmental Sustainability

Animal agriculture is one of the biggest drivers of environmental destruction.

- “Did you know the UN called meat ‘the world’s most urgent problem’ due to its environmental impact?”

- “Since animal agriculture contributes at least as much to climate change than the entire transportation sector, how do you think food choices impact the planet?”

Why? This reframes veganism as a solution to environmental crises, not just an individual choice.

Expose the Reality of Animal Agriculture

Many people don’t realize the scale of suffering farmed animals endure.

- “Are you aware that over 70 billion land animals are slaughtered every year for food—more than the total number of humans who have ever lived?”

- “Labels like ‘cage-free’ and ‘humane-certified’ often mislead consumers—would it surprise you that most of these animals still endure extreme suffering?”

Why? This encourages people to question the humane myth and reconsider their participation.

Frame Veganism as a Social Justice Issue for Humans and Other Animals

It challenges all forms of oppression and systems that harm marginalized communities.

- “Can you see that all forms of oppression are related, whether inflicted on humans or other animals. “

- “Did you know slaughterhouse workers suffer PTSD-like symptoms from killing animals every day?”

- “Factory farms disproportionately pollute poor communities. Does it seem fair that low-income areas suffer from the waste of industrial farms?”

Why? This helps connect veganism to other justice movements, making it more relevant.

Show That All Major Ethical Philosophies Support Veganism

No matter what ethical framework someone follows, it leads to rejecting animal exploitation.

- “Rights-based ethics say sentient beings deserve respect and the right to live their lives without human oppression. If animals are ‘subjects of a life,’ don’t they deserve the same moral consideration?”

- “Utilitarianism says we should minimize suffering. Since animal agriculture causes immense suffering, doesn’t that mean we should avoid it?”

Why? This forces them to reconcile their beliefs with their food choices.

Make It Clear That Going Vegan Is Easier Than Ever

People resist veganism because they assume it’s too hard.

- “With plant-based options everywhere, do you think going vegan today is harder than it was ten years ago?”

- “If I could show you easy ways to transition, would you be open to trying it for a week?”

Why? This makes veganism feel practical and achievable.

Leave Them With a Thought-Provoking Question

Instead of arguing, leave them with a question that challenges their perspective.

- “If you can live a healthy life without contributing to suffering, what’s stopping you?”

- “What’s the biggest barrier for you in considering veganism? I’d love to hear your thoughts.”

Why? This keeps the conversation open and encourages self-reflection.

Footnotes

Our sources, with links back to where they are used.

- Magee, Bryan. The Story of Philosophy. DK Pub., 1998. 15 ↩︎

- Huffman, Carl. “Pythagoras.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2014. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2014. ↩︎

- Zaraska, Marta. Meathooked: The History and Science of Our 2.5-Million-Year Obsession with Meat. 1 edition. New York: Basic Books, 2016. 119-120 ↩︎

- White, Michael. Leonardo: The First Scientist. 1st edition. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000, 131 ↩︎

- White, Michael. Leonardo: The First Scientist. 1st edition. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000, 131 ↩︎

- Horowitz, David. “History of Vegetarianism – Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519).” International Vegetarian Union, July 19, 2002. ↩︎

- McCurdy, Edward. The Mind of Leonardo Da Vinci. Dover Ed edition. Dover Publications, 2013, 78. ↩︎

- Jones, Michael Owen. “In Pursuit of Percy Shelley, “The First Celebrity Vegan”: An Essay on Meat, Sex, and Broccoli.” Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 53 no. 2, 2016, p. 1-30. Project MUSE. ↩︎

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. A Vindication of Natural Diet. Percy Bysshe Shelley. A public domain book. Vegetarian Society, 1884. A Public Domain Book. 25. ↩︎

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. A Vindication of Natural Diet. Percy Bysshe Shelley. A public domain book. Vegetarian Society, 1884. A Public Domain Book. 25 ↩︎

- Tolstoy, Leo. 1900. The First Step: An Essay on the Morals of Diet, to Which Are Added Two Stories. Albert Broadbent. 61, 6 ↩︎

- Tolstoy, Leo. 1900. The First Step: An Essay on the Morals of Diet, to Which Are Added Two Stories. Albert Broadbent. 61, 6 ↩︎

- Tolstoy, Leo. 1900. The First Step: An Essay on the Morals of Diet, to Which Are Added Two Stories. Albert Broadbent. 58-59 ↩︎

- Richards, Jennie. “George Bernard Shaw Poem, ‘We Are The Living Graves of Murdered Beasts.’” Humane Decisions, January 15, 2015. ↩︎

- Richards, Jennie. “George Bernard Shaw Poem, ‘We Are The Living Graves of Murdered Beasts.’” Humane Decisions, January 15, 2015. ↩︎

- Gandhi, Mahatma. “Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth.” Courier Corporation, 1948, 208..

↩︎ - Gandhi, Mahatma. “Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth.” Accessed February 3, 2018. 52. ↩︎

- Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869-1948).” International Vegetarian Union. Accessed October 16, 2017. ↩︎

- “History.” The Vegan Society, 2019. Accessed 7 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- “History.” The Vegan Society, 2019. Accessed 7 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- “History.” The Vegan Society, 2019. Accessed 7 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- Watson, Donald. “The Vegan News – No. 1.” UK Veggie, November 1944. ↩︎

- The Vegan Society. “The Vegan Society.” The Vegan Society, 2022. ↩︎

- Watson, Donald. “The Vegan News – No. 1.” UK Veggie, November 1944. ↩︎

- O’keffee, Jill. “The Inhumane Psychological Treatment of Factory Farmed Animals | New Roots Institute”. ↩︎

- Shields, Sara J., and A. B. M. Raj. “A Critical Review of Electrical Water-Bath Stun Systems for Poultry Slaughter and Recent Developments in Alternative Technologies.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science13, no. 4 (September 17, 2010): 281–99. ↩︎

- Pitney, Nico. “Scientists Believe The Chickens We Eat Are Being Slaughtered While Conscious.” HuffPost, 24:58 400AD. ↩︎

- Welfare at Slaughter of Broiler Chickens: A Review.” Accessed June 12, 2019. ↩︎

- Warrick, Jo. “‘They Die Piece by Piece.’” Washington Post, April 10, 2001. Accessed December 3, 2019 ↩︎

- Mood, Alison. “Worse Things Happen at Sea: The Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish.” fishcount.org.uk, 2010 ↩︎

- “The Stunning and Killing of Pigs“, Humane Slaughter Association, May 2007 ↩︎

- “Is Gas Killing the Pig Industry’s Darkest Secret?“, Phillip Lymbery, November 11, 2021 ↩︎

- Matthew Zampa, “There’s Nothing “Humane” About Killing Pigs in Gas Chambers,” Sentient Media, November 12, 2019 ↩︎

- “Overview of Cattle Laws | Animal Legal & Historical Center.” Accessed November 28, 2019. ↩︎

- Haarlem, R. P. van, R. L. Desjardins, Z. Gao, T. K. Flesch, and X. Li. “Methane and Ammonia Emissions from a Beef Feedlot in Western Canada for a Twelve-Day Period in the Fall.” Canadian Journal of Animal Science 88, no. 4 (December 2008): 641–49. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- Fox, Michael. “Factory Farming.” The Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy, 1980 ↩︎

- Gregory, Neville G., and Temple Grandin. Animal Welfare and Meat Science. Oxon, UK ; New York, NY, USA: CABI Pub, 1998. 209-10. ↩︎

- Stevenson, Peter, Compassion in World Farming (Organization), and World Society for the Protection of Animals. Closed Waters: The Welfare of Farmed Atlantic Salmon, Rainbow Trout, Atlantic Cod and Atlantic Halibut. Godalming, Surrey: Compassion in World Farming, 2007. ↩︎

- Consumer Reports Greener Choices. “Cage-free on a package of chicken: Does It Add Value?” March 5, 2018. ↩︎

- Welfare Implications of Beak Trimming.” American Veterinary Medical Association, February 7, 2010 ↩︎

- See https://vbriefings.org/pig-injustices for citations. ↩︎

- “Changes in Dairy Cattle Health and Management Practices in the United States,1996-2007.” Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, July 2009. Accessed 3 December 2019 ↩︎

- News, A. B. C. “Dehorning: ‘Standard Practice’ on Dairy Farms.” ABC News. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- Robbins, Ja, Dm Weary, Ca Schuppli, and Mag von Keyserlingk. “Stakeholder Views on Treating Pain Due to Dehorning Dairy Calves.” Animal Welfare 24, no. 4 (November 14, 2015): 399–406. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- USDA: Reference of Beef Cow-calf Management Practices in the United States, 2007–08 ↩︎

- “Castration of Calves.” Accessed November 19, 2019 ↩︎

- Robertson, I.S., J.E. Kent, and V. Molony. “Effect of Different Methods of Castration on Behaviour and Plasma Cortisol in Calves of Three Ages.” Research in Veterinary Science 56, no. 1 (January 1994): 8–17. Accessed December 3, 2019 ↩︎

- Marchant-Forde, Jeremy N., Ruth M. Marchant-Forde, and Daniel M. Weary. “Responses of Dairy Cows and Calves to Each Other’s Vocalisations after Early Separation.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 78, no. 1 (August 2002): 19–28. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- Wagner, Kathrin, Daniel Seitner, Kerstin Barth, Rupert Palme, Andreas Futschik, and Susanne Waiblinger. “Effects of Mother versus Artificial Rearing during the First 12 Weeks of Life on Challenge Responses of Dairy Cows.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 164 (March 2015): 1–11. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- Prescott, N.B. and Wathes, C.M., (2002). Preference and motivation of laying hens to eat under different illuminances and the effect of illuminance on eating behavior. British Poultry Science, 43: 190-195 ↩︎

- Eugen, Kaya von, Rebecca E. Nordquist, Elly Zeinstra, and Franz Josef van der Staay. “Stocking Density Affects Stress and Anxious Behavior in the Laying Hen Chick During Rearing.” Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI9, no. 2 (February 10, 2019). ↩︎

- Marino, Lori. “Thinking Chickens: A Review of Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior in the Domestic Chicken.” Animal Cognition20, no. 2 (2017): 127–47. ↩︎

- Appleby, M.C. “What Causes Crowding? Effects of Space, Facilities and Group Size on Behavior, with Particular Reference to Furnished Cages for Hens.” Animal Welfare13 (August 1, 2004): 313–20. ↩︎

- Cheng, H.-W. “Breeding of Tomorrow’s Chickens to Improve Well-Being.” Poultry Science 89, no. 4 (April 1, 2010): 805–13 ↩︎

- Jamieson, Alastair. “Large Eggs Cause Pain and Stress to Hens, Shoppers Are Told,” March 11, 2009, sec. Finance ↩︎

- Hartcher, K.M., and H.K. Lum. “Genetic Selection of Broilers and Welfare Consequences: A Review.” World’s Poultry Science Journal, vol. 76, no. 1, 21 Dec. 2019, pp. 154–167. ↩︎

- Prunier, A., M. Heinonen, and H. Quesnel. “High Physiological Demands in Intensively Raised Pigs: Impact on Health and Welfare.” Animal 4, no. 6 (June 2010): 886–98. ↩︎

- Prunier, A., M. Heinonen, and H. Quesnel. “High Physiological Demands in Intensively Raised Pigs: Impact on Health and Welfare.” Animal 4, no. 6 (June 2010): 886–98. ↩︎

- Broom, Donald. “The Roles of Industry and Science, including genetic selection, in improving animal welfare,” Animal Science and Biotechnologies 42, no. 2 (2009): 532–46. ↩︎

- Prunier, A., M. Heinonen, and H. Quesnel. “High Physiological Demands in Intensively Raised Pigs: Impact on Health and Welfare.” Animal 4, no. 6 (June 2010): 886–98. ↩︎

- Webster, John. Animal Welfare. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2000. 88, 139-140. ↩︎

- Colorado State Animal Science, “Semen Collection from Bulls.” September 2, 2002 ↩︎

- Rajala-Schultz, Gustavo M. Schuenemann, Santiago Bas, Armando Hoet, Eric Gordon, Donald Sanders, Klibs N. Galvão and Päivi. “A.I. Cover Sheaths Improved Fertility in Lactating Dairy Cows.” Progressive Dairy. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- The Beef Site. “Artificial Insemination for Beef Cattle.” Accessed November 29, 2019. ↩︎

- Chickens Suffer during Catching, Loading, and Transport.” Accessed June 12, 2019 ↩︎

- Jacobs, Leonie, Evelyne Delezie, Luc Duchateau, Klara Goethals, and Frank A. M. Tuyttens. “Impact of the Separate Pre-Slaughter Stages on Broiler Chicken Welfare. ↩︎

- “WATCH: Criminal Animal Abuse Caught on Video at Walmart Pork Supplier,” Mercy for Animals, May 6, 2015 ↩︎

- One can find numerous pig abuse videos from multiple sources with this search ↩︎

- “The Horrifying Truth About Pig Farms,” NowThis February 25, 2020 ↩︎

- Slaughterhouse Investigation: Cruel and Unhealthy Practices. Humane Society of the United States, Youtube, 2008. Accessed December 3, 2019. ↩︎

- “Cattle abuse wasn’t rare occurrence“, ABC New ↩︎

- Guest Contributor. “Watch: A Dairy Industry Exposé: Death, Cages and Downers.” The London Economic, 9 May 2018, www.thelondoneconomic.com/must-reads/a-dairy-industry-expose-death-cages-and-downers-88240/. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- “WATCH: Criminal Animal Abuse Caught on Video at Walmart Pork Supplier,” Mercy for Animals, May 6, 2015 ↩︎

- “Age of Animals Slaughtered,” Farm Transparency Project, October 12, 2017. ↩︎

- “Age of Animals Slaughtered,” Farm Transparency Project, October 12, 2017. ↩︎

- “Age of Animals Slaughtered,” Farm Transparency Project, October 12, 2017. ↩︎

- What Happens with Male Chicks in the Egg Industry? – RSPCA Knowledgebase. ↩︎

- “Age of Animals Slaughtered,” Farm Transparency Project, October 12, 2017. ↩︎

- “Age of Animals Slaughtered,” Farm Transparency Project, October 12, 2017. ↩︎

- “The Dirt on Humanewashing | Publications.” Farm Forward, 13 Dec. 2020. ↩︎

- Investigations were carried out in 2016 by Consumer Reports and published on various pages of their greenchoices.org website. These pages have since been removed, but can reached from this archive link. ↩︎

- Investigations were carried out in 2016 by Consumer Reports and published on various pages of their greenchoices.org website. These pages have since been removed, but can reached from this archive link. ↩︎

- “Global Animal Partnership — General Support (2016) | Open Philanthropy.” Open Philanthropy, 30 July 2024, www.openphilanthropy.org/grants/global-animal-partnership-general-support-2016/. Accessed 28 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- “The Dirt on Humanewashing | Publications.” Farm Forward, 13 Dec. 2020. ↩︎

- Derived from United Nations FAO statistics for 2017: “FAOSTAT.” ↩︎

- “US Factory Farming Estimates.” Sentience Institute. Accessed 2022-06-23 ↩︎

- Kaneda, Toshiko, and Carl Haub. “How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth?” PRB, 15 Nov 2022. ↩︎

- Derived from United Nations FAO statistics for 2017: “FAOSTAT.” ↩︎

- Estimates are from United Nations FAO data compiled by Fishcount UK. Fish Count UK: “Estimated Numbers of Individuals in Annual Global Capture Tonnage (FAO) of Fish Species (2007 – 2016)“; “Estimated Numbers of Individuals in Global Aquaculture Production (FAO) of Fish Species (2017)“; “Estimated numbers of individuals in average annual fish capture (FAO) by country fishing fleets (2007 – 2016)”; “Estimated numbers of individuals in aquaculture production (FAO) of fish species (2017).” ↩︎

- Marina Bolotnikova provided solid visual evidence for this quote in “Forget They Are an Animal”, Current Affairs, August 2022 ↩︎

- Marina Bolotnikova provided solid visual evidence for this quote in “Forget They Are an Animal”, Current Affairs, August 2022 ↩︎

- “Vegetarian Diet: How to Get the Best Nutrition.” Mayo Clinic. Accessed August 2, 2017. ↩︎

- “Becoming a Vegetarian.” Harvard Health Publications Harvard Medical School, March 18, 2016. ↩︎

- “Understanding Vegetarianism & Heart Health.” Cleveland Clinic, December 2013. ↩︎

- Phillip J Tuso, MD, Mohamed H Ismail, MD, Benjamin P Ha, MD, and Carole Bartolotto, MD, RD. “Nutritional Update for Physicians: Plant-Based Diets.” The Permanente Journal – The Permanente Press – Kaiser Permanente – Permanente Medical Groups, 2013. ↩︎

- Ask A Nutritionist: Plant-Based Diets.” NewYork-Presbyterian, March 30, 2017 ↩︎

- “Understanding Vegetarianism & Heart Health.” Cleveland Clinic, December 2013. ↩︎

- Phillip J Tuso, MD, Mohamed H Ismail, MD, Benjamin P Ha, MD, and Carole Bartolotto, MD, RD. “Nutritional Update for Physicians: Plant-Based Diets.” The Permanente Journal – The Permanente Press – Kaiser Permanente – Permanente Medical Groups, 2013. ↩︎

- “About Us.” Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Accessed August 2, 2017. ↩︎

- Raj, Sudha, et al. “Vegetarian Dietary Patterns for Adults: A Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.” PDF. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 7 Feb. 2025. ↩︎

- “Healthy Eating Guidelines for Vegans.” Dietitians of Canada, November 2017. ↩︎

- “British Dietetic Association.” The Vegan Society. Accessed August 3, 2017. ↩︎

- “Vegan Diets: Everything You Need to Know – Dietitians Association of Australia.” Dietitians Association of Australia. Accessed August 3, 2017. ↩︎

- The PlantPure Nation documentary video can be watched free on Tubi and Amazon Prime Video, and is also available for rent or purchase on Amazon Video, Google Play Movies, YouTube, and Apple. ↩︎

- The PlantPure Nation documentary video can be watched free on Tubi and Amazon Prime Video, and is also available for rent or purchase on Amazon Video, Google Play Movies, YouTube, and Apple. ↩︎

- Ornish, Dean. “Ornish Reversal Program.” Ornish Lifestyle Medicine, ↩︎

CDC. “Leading Causes of Death.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 May 2024. ↩︎ - “Intensive Cardiac Rehabilitation (ICR) Programs | CMS.” Cms.gov, 2014. Accessed 12 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- UCLA Health. Scientifically Proven Research for the Dr. Dean Ornish Program for Reversing Heart Disease. ↩︎

↩︎ - UNEP Article 2018, “Tackling the world’s most urgent problem: meat,” Accessed 2022-05-21 ↩︎

- World Watch Magazine July-August 2004 via The Face on Your Plate: The Truth About Food, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson · 2010. 57, Google Books, Accessed 2022-06-20 ↩︎

- Christopher Hyner. “A Leading Cause of Everything: One Industry That Is Destroying Our Planet and Our Ability to Thrive on It.” Georgetown Environmental Law Review, October 23, 2015. ↩︎

- Wilson, Lindsay. “The Carbon Foodprint of 5 Diets Compared.” Shrink That Footprint, 28 June 2022. ↩︎

- Scarborough, P., Clark, M., Cobiac, L. et al. Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. Nat Food 4, 565–574 (2023) via Yale Environment 360 ↩︎

- vBriefings. The Environmental Impact of Animal Agriculture.Section. 2024. ↩︎

- “Cattle Ranching in the Amazon Region | Yale School of the Environment,Global Forest Atlas.”Accessed 19 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- “Margulis, Sergio. 2004. Causes of Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. World Bank Working Paper;No. 22. © Washington, DC: World Bank. ↩︎

- Asner, Gregory P., et al. “GRAZING SYSTEMS, ECOSYSTEM RESPONSES, and GLOBAL CHANGE.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 29, no. 1, 21 Nov. 2004, pp. 261–299. ↩︎

- Springmann, M., Van Dingenen, R., Vandyck, T. et al. The global and regional air quality impacts of dietary change. Nat Commun 14, 6227 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41789-3 ↩︎

- Hannah Ritchie (2022) – “Wild mammals make up only a few percent of the world’s mammals” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. ↩︎

- James Rowe and John Nolan, Energy Requirements of Livestock. The Theory and Practice of Animal Nutrition, Applied Animal Nutrition Journal 2009 ↩︎

- The 24 to 1 figure was calculated from the table on page 37, figure 12, by averaging the ratios of calories in to calories out among the different animal products. For example, pigs consume 10 calories to get one calorie of pork out (100/10). If you average beef (100), milk (14), shrimp (14), pork (10), chicken (9), fin fish (8), and egg (13), you get 24. If sheep and buffalo milk were included, the average would be even more concerning.. “Creating a Sustainable Food Future.” World Resources Institute, 2013-2014. ↩︎

- Poore, J., and T. Nemecek. “Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers.” Science 360, no. 6392 (June 2018): 987–92 ↩︎

- UNEP Analysis 2010, Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production Accessed 2022-05-20 ↩︎

- Pritchett, Liam. “David Attenborough Wants You to Go Plant-Based for the Planet.” LIVEKINDLY, 26 Aug. 2020. Accessed 20 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- Roome, John. “Rapid, Climate-Informed Development Needed to Keep Climate Change from Pushing More than 100 Million People into Poverty by 2030.” World Bank, 2015. ↩︎

- Heanue, Oscar. “For Slaughterhouse Workers, Physical Injuries Are Only the Beginning.” OnLabor, 17 Jan. 2022. ↩︎

- Fitzgerald, Amy J., Linda Kalof, and Thomas Dietz. “Slaughterhouses and Increased Crime Rates: An Empirical Analysis of the Spillover From ‘The Jungle’ Into the Surrounding Community.” Organization & Environment 22, no. 2 (June 2009): 158–84. Accessed December 3 2019. ↩︎

- Bernard, Sara. “Giant Hog Farms Are Making People Sick. Here’s Why It’s a Civil Rights Issue.” Grist, Grist, 6 Nov. 2014. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- Newsome, Melba. “Decades of Legal Battles over Pollution by Industrial Hog Farms Haven’t Changed Much for Eastern NC Residents Burdened by Environmental Racism.” North Carolina Health News, 29 Oct. 2021. ↩︎

- Watson, Donald. “The Vegan News – No. 1.” UK Veggie, November 1944. ↩︎

- Dunayer, Joan. Animal Equality: Language and Liberation. Ryce Publishing, 2001. ↩︎

- Gaard, Greta. Ecofeminism: Women, Animals, Nature. Temple University Press, 1993. ↩︎

- Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2010 ↩︎

- Harper, A. Breeze, ed. Sistah Vegan: Black Female Vegans Speak on Food, Identity, Health, and Society. Lantern Books, 2010. ↩︎

- Taylor, Ryan. “Joaquin Phoenix Oscar Acceptance Speech Transcript: Phoenix Wins for Joker | Rev.” Rev, 10 Feb. 2020. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024. ↩︎

- Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights. University of California Press, 1983. ↩︎

- Tom Regan Speech at the Royal Institute of Great Britain in 1989. ↩︎

- Evans, Richard. “Understanding Utilitarianism: A Guide.” Philosophos.org, 22 June 2023. ↩︎

- Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. 1789. Reprinted by Oxford University Press, 1907. ↩︎

- Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation. HarperCollins, 1975 ↩︎

- Rueter, Sondra. “Virtue Ethics: What It Is and How It Works.” Philosophos.org, 3 May 2023. ↩︎

- Hursthouse, Rosalind. “The virtue ethics defense of animals.” The Practice of Virtue: Classic and Contemporary Readings in Virtue Ethics, edited by Jennifer Welchman, Hackett Publishing, 2006, pp. 136-155. ↩︎

- D’Olimpio, Laura. “Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care.” The Ethics Centre, 13 May 2019, ethics.org.au/ethics-explainer-ethics-of-care/. ↩︎

- Noddings, Nel. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. 2nd ed., University of California Press, 2003. ↩︎

- Salazar, Maria. “Effects of Diet Choices.” Animal Charity Evaluators, Feb. 2021. ↩︎

- “Vegan Calculator” Vegan Calculator, 2019, Accessed August 31, 2024. ↩︎

- VeganRevolution. It’s a New Era of Veganism— Game Changers First Trailer YouTube, Accessed May 27, 2018. Veganism is going mainstream. ↩︎

- “Vegan Is Going Mainstream, Trend Data Suggests.” Accessed November 15, 2017 ↩︎

- “Top Trends in Prepared Foods 2017: Exploring Trends in Meat, Fish and Seafood; Pasta, Noodles and Rice; Prepared Meals; Savory Deli Food; Soup; and Meat Substitutes.” Global Data, June 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017. ↩︎